Why Cristobal Balenciaga is the greatest couturier of all time.

Сristobal Balenciaga is buried in a small, old cemetery located on a mountain above the medieval fishing village of Getaria where he was born and grew up on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean in the land of the Basques. He is buried in the family grave. You can barely find his name on the huge marble grave stone, faded and lost among the numerous members of this large Basque family.

He was a strict Basque Catholic, which was something that defined his life, his career and his design aesthetics. He was shy and quiet-spoken, he gave a single interview in his entire life, right after closing his house in 1968. He lived as a hermit: his only public appearance was at Chanel’s funeral in 1971, a year before his death. The people close to him remember him as a reclusive, even paranoid man. And it was this respectable, religious, stiff and old-fashioned perfectionist who created the entire modern fashion.

In principle, all great couturiers in the history of fashion are divided into two groups. Those who turned women into objects of their fantasies: such as flowers in case of Dior, or odalisques in the case of Poiret; and those who didn’t make women into anything but instead broadened their horizons by showing them the way of simplicity (like Chanel) or futurism (like Balenciaga.) It’s a common mistake to think that futurism is something very fussy, metallic and Barbarella-esque, while in fact it’s just a search for new shapes and forms. Balenciaga was a true futurist in that sense. Although at the same time his main artistic principle was to cut out all the excessive details that didn’t contribute to the pure simplicity. This was his way achieving perfection, and it worked quite well. The culmination of his work became the famous, black rectangular dress with origami-like folds and pearl shoulder-straps.

During the 1920’s, 1930’s and 1940’s he was already a true master whose every dress was a genuine perfection: a phenomenal fit later dubbed architectural, fantastic work with embroidery and lace, signature colour combinations and patterns, and his characteristic perfectionism when a dress looks significant but doesn’t outshine the client instead emphasizing her beauty. But it is in the early 1950’s that he becomes an unreachable genius: in a way, this outburst of genius was a reaction against the decorative aesthetic of Dior’s “flower women” that was alien to him (the same mechanism later worked with Chanel, when her irritation with Dior facilitated her fashion come-back). But this is just one side of the story: Balenciaga’s entire journey, his perfectionism and minimalism, all led to this triumph.

The pivotal silhouette of the 1950’s, the base of Dior’s “new look”, was the exaggerated “femininity”. Dior hides the waist in a corset; attaches special cushions to his skirts and expends up to 80 meters of silk on the hoop skits to achieve the desired ‘hour glass’ silhouette. Balenciaga moves in the opposite direction, away from the new-look, and the more he detaches himself from it, the more stunning his collections become.

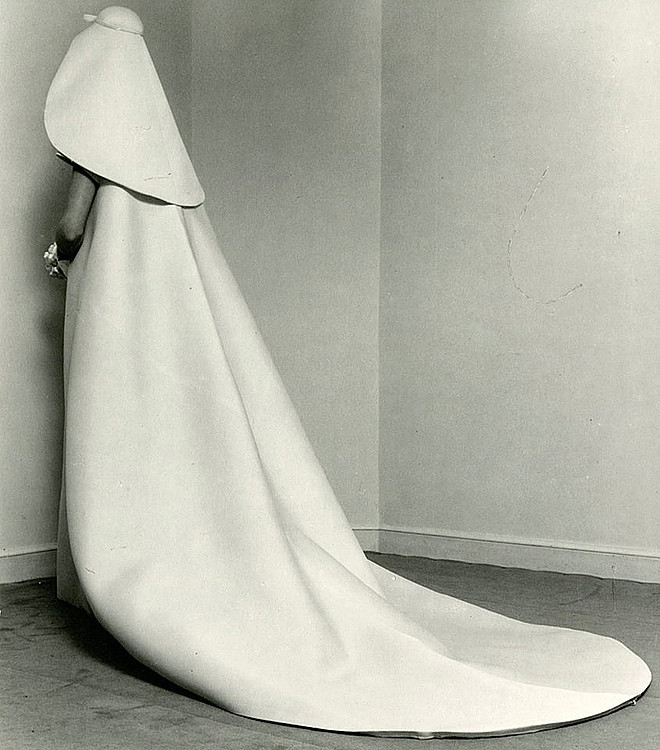

Tunic dresses with loose waists in 1955, baggy dresses where the waist is moved as low as possible, forming a bubble on the back in 1957; baby doll dresses with no waistline at all in 1958. These dresses created extra volume around the body as he didn’t like close fitting clothing.

His legendary balloon jackets, cocoon dresses, and peacock dresses attracted many famous clients, from Maria Callas, Grace Kelly, Queen Fabiola of Belgium, numerous countesses, marquises and duchesses; to Rachel Mellon, the wife of Paul Mellon, a famous American philanthropist and collector. Furthermore they turned Balenciaga into a fashion icon. Everything he presented in the 1950’s and the 1960’s, up until the closing his house at the first signs of the student protests in 1968, was directed towards the future and even today looks mind-blowingly bold.

The tiny “hairdresser” dresses that made Ungaro famous, André Courrèges’ futuristic minis (both men used to be Balenciaga’s assistants), trapeze dresses that set off the triumph of the young Yves Saint Laurent – all of these were to become the new fashion in the 1960’s, literally blowing away the world of traditional sewing. And this, although the outcome was different from his detached perfection, would be impossible without Cristobal Balenciaga. His work during the last 15 years of his career broke outside the fashion boundaries of that time and contemporary fashion often borrows from his legacy.

Balenciaga couture dress

This black and gold lace dress

with a solid gazar silk underdress, a fabric specially designed by a Swiss textile manufacturer Adraham for Balenciaga’s sculptural fits, is a true masterpiece of Balenciaga’s late minimalism without a single excessive detail, extra undercut or stitch. Balenciaga’s fit wasn’t just skillful, it was impeccable, this dress being a perfect example of it. It’s refined and mind-blowing in its simplicity. And of course, discovering a couture Balenciaga piece today (both from his Spanish brand Eisa and the Parisian Balenciaga) is rare like finding a Zurbarán painting that his dresses resemble so much.

The greatness of any couturier is not only defined by the extent of which his silhouettes determine the style of the elite and glossy magazines of his time, but also the extent to which it shaped the fashion and the people on the streets. Cristobal Balenciaga, the uptight aesthete and solitary genius, came up with the silhouettes that keep coming back for more than five decades, and will keep coming back for at least as long.